I have an issue with the term “collecting”’

The Costa Rican entrepreneur puts social impact at the heart of his art-buying.

Luis Javier Castro photographed in Parque de la Libertad, Costa Rica, in 2019 © Alonso Tenorio.

By Georgina Adam

When we were setting up our call, the Latin American entrepreneur and art collector Luis Javier Castro told me: “It’s not my style to display luxury and fashion.” Indeed, during our conversation a few days later, it became clear that his art collecting is not about showing off but has a far more intellectual reach. It is deeply connected to his work on social initiatives in his region.

Yet there was a phase in his life when Castro indulged in what he now calls “ego collecting”. He achieved early success in business, before he was 35, and had to have a “name on the walls”. He bought art by well-known Latin American artists — Beatriz Milhazes, Fernando Botéro, Guillermo Kuitca. “I suppose I was a bit Master of the Universe at the time,” he laughs, while modestly pointing out that this was in a small place, Costa Rica.

But, he says, he felt a bit empty — “I wasn’t enjoying it” — and a friend warned he was losing the “essence” he had as a child. He reacted by reading more, meditating and following the Chinese practice of Qigong. “I became more inside myself, I rediscovered myself,” he says. From then on his collecting changed, and became focused on the process of artistic creation: as a result his acquisitions today are highly conceptual with a strong emphasis on video and performance works.

We talk over WhatsApp: he is in his Bogotá home, where he spends part of his time; I am locked down in the UK. Dressed simply in a open-necked blue shirt and grey jacket, his grey hair swept back, he is friendly and jovial, laughing often and gesturing with his hands to make his points.

He was born to a comfortably-off Costa Rican family in 1966, and an early influence was his uncle Carlos Lachner, whom Castro describes as “a true Renaissance man, a songwriter, an artist and a promoter of the arts”. Lachner believed that in the 1980s, Costa Rican artists were only producing what buyers wanted, not what they wanted to make. So he instituted and funded a collection to buy art from young artists, and put Castro on the acquisitions committee, at the age of just 15, alongside experts and a representative of the Ministry of Culture.

Working with a small budget — “Costa Rican art was not expensive at all” — the committee examined dozens of works of art every month. “That was a very interesting experience, it helped me understand where ideas come from and the similarities between the artistic and entrepreneurial processes,” says Castro.

After a period working for the management consultants Bain & Co, in 1996 Castro co-founded his own private equity firm, Mesoamerica, with the aim of “conscious capitalism, putting purpose at the centre of what we do”. He explains, “We invest in important transformational projects, including renewable energy, telecoms, construction or restaurants — we have 500 of these in Colombia and Chile.” His guiding principle, he says, is “to do well by doing good”, and developing the role of the private sector in society as a way of tackling the issues of the Latin American region.

The company did well, and now the firms it owns have some 20,000 employees. But at its inception, I ask, did anyone understand his concerns? “Sure, no one invited me to parties!” He laughs out loud, adding more seriously, “People didn’t see me as threatening, but rather as dissonant. I was fighting against the concept that companies are just for making profit. They need to, of course, to stay alive, but that should not be their only purpose.”

He has since become involved in many social impact initiatives: he is on the board of United Way Worldwide, the largest privately funded non-profit organisation in the world, he helped found the public-private human development Fundación Parque de la Libertad in Costa Rica, and was the enabler in establishing the Costa Rican hub of the Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design which offers training on design in the broadest sense. He is a member of Tate’s Latin American Committee and funds a prize for the best Colombian artist at ARTBO, Bogotá’s annual art fair. He has been named “entrepreneur of the year” twice (in 2013 and 2019) by El Financiero, a Costa Rican financial newspaper.

He tells me that he sees art and entrepreneurship as intimately linked — and he knits his fingers together to demonstrate. “Sometimes when we are deciding how to invest, I take my team to artists’ studios, to demonstrate how the creative processes are so interconnected,” he says.

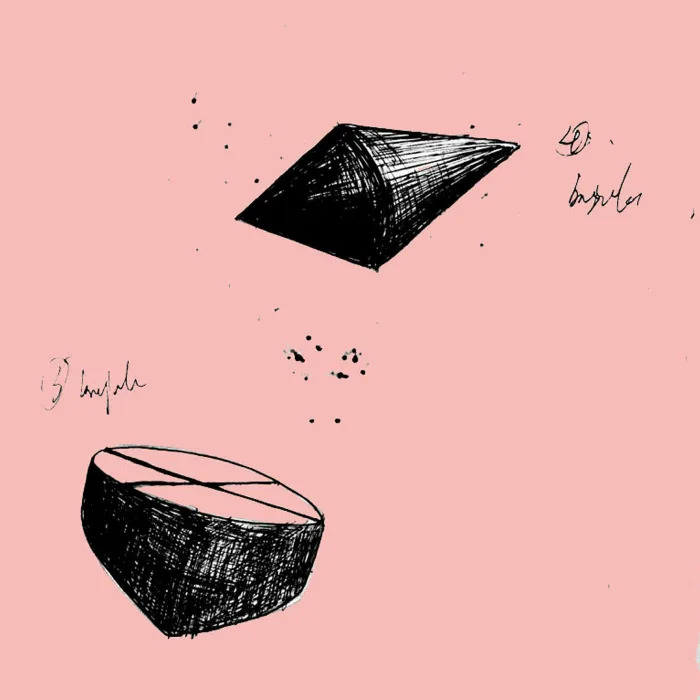

“I am more a collector of ‘processes’ than of objects,” he tells me, explaining “I really want to understand the whole method, from the idea to its realisation. My collection is very conceptual, very experimental.” An example is “Las Frecuencias que me hacen”, a performance piece by Maria José Arjona, shown at the Cali Bienale in 2017. “I bought the performance, I have the dress she wore when presenting it, but I also have the ‘archive of the future’, the objects she prepared before the piece was even performed . . . I like to be part of this sort of mind- boggling thing!” he exclaims.

Another five works in his collection — which numbers about 500 items — are by the Spanish-American Daniel Canogar. “Cannula” (2016) is made by putting a word in a computer. It then searches in YouTube for videos with that word, from which an algorithm is produced to create a work of art, which as a result changes constantly.

Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary.

Castro has a close friendship with the Colombian artist Oscar Muñoz, who founded Lugar a Dudas (Room for Doubts), an art centre for young emerging artists. When Castro bought Muñoz’s “El Coleccionista” (2014) — a 12-metre video work showing a hologram of the artist arranging his photography collection — he asked for 50 per cent of the price to go to fund the space, and the other 50 per cent to FLORA ars+natura, the artistic space founded by the Colombian curator José Roca, whom he cites as a major influence. He is proud of how his initiatives have helped emerging artists from difficult backgrounds, citing the Costa Rican Christian Salablanca Díaz, whose video “Geometría del centro” (Geometry of the Centre) (2020) is currently on show in the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum in Madrid.

Beside him as we talk is part of “Cofia” (2016), a large installation made of balls of human hair by the Colombian artist Juan Fernando Herrán: the whole piece measures three by eight metres. “This will go to a museum, I will have it in my home just for a year or so,” says Castro. Another work is destined for the Parque de la Liberdad: Clemencia Echeverri’s 2007 “Treno”, a video of the Cauca river in Colombia.

“I would like, somehow, to give an example of my way of collecting,” he continues. “I don’t like to put art in storage, I like to loan it and show it. My house is designed like a white canvas that can accept a lot of art, and I take a lot of museum groups around. I even have an issue with the term ‘collecting’ — if it is only about accumulating. Other people may have interaction with art as a business, that’s fine, but I don’t do that.

“I have never resold a single piece in my life,” he concludes.